I finally read Lost at Sea a week ago, and I haven’t known yet what to say about it. It’s Bryan Lee O’Malley’s first graphic novel, and like many first novels it’s about finding yourself. Raleigh, the protagonist and narrator, has just graduated from high school and taken a trip to California, where she finds herself getting a ride home to Canada with some other kids she knew vaguely from school. And so she’s stalked by cats and searching for her soul and her other half (and her original half, really) and the link between an ambiguous past and a frighteningly open future. And it’s about me, at least when I read it. It’s one in a long series of books that have seemed to have mystical import, to get at some truth of how I see (or, in this case, saw) the world, and in some sense that’s what Lost at Sea is really all about. It’s not a harbinger of doom like Bridge to Terabithia seemed to be when I was a short-haired 9-year-old who already had built a Narnia in the woods with my fundamentalist neighbor, not something where the details match. It’s more like an antidote to The Catcher in the Rye, which I hated as a teenager because it seemed so unrealistic. Holden Caulfield wouldn’t just start out by owning up to his own phoniness. After all, what made being a teenager (and, ok, sometimes being me now) so painful was not that everyone else was phony but that they were phony and still managed to be more authentic than I was. And Raleigh understands this, and her carmates, Stephanie, Ian and Dave, seem to have some sort of understanding themselves. But I never found myself on a road trip before college and my mother certainly didn’t sell my soul when I was 11 (although that was the year that whatever I had instead of a soul fell apart) and I’m forced to admit that Lost at Sea can’t be a story about me. What it is, though, and what may have kept it from being commercially successful, is a story about “I.”

Oh, there’s a “you,” too, and there always is in these sorts of stories, right? It’s never entirely clear who “you” is, whether it’s just another version of “I”/Raleigh or “I”/Rose/reader or the “you” Raleigh wants to address and wishes she could address with the depth he deserves. Am I being oblique enough? I hope so, because Lost at Sea is a story about the unknowability of everyone and everything. It’s about connections that seem superficial but turn out to be vast and tight and about connections that seem meaningful despite their superficiality, like my insistence that Raleigh is a sort of me despite the fact that nothing that happens matches. The story is an epic of subjectivity, told unerringly in Raleigh’s voice and with her limited and self-restricted perspective. The one place it falters is on the last page, as Raleigh (or perhaps O’Malley) steps back too far and thinks that she (or he, of course) can see things as they are enough to sum up at least the uncertainty. It’s an unnecessary concretization, but not an uncharacteristic one, because Raleigh began the book with strong predetermined notions about herself and her life and she ends it with changed views, but she’s only leaving on another trip somewhere into her future, and she’s got plenty of time to grow up. (And so do I, I hope.)

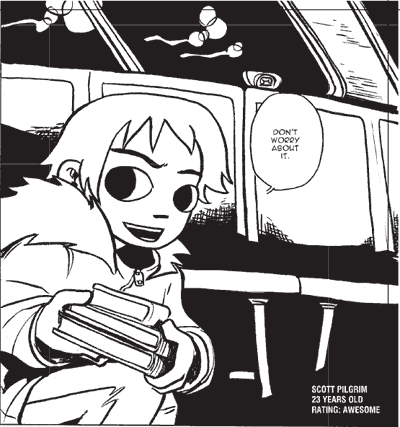

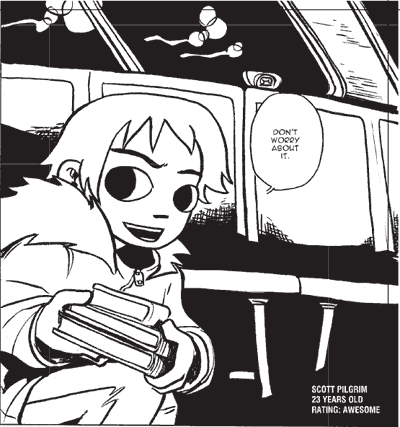

Scott Pilgrim’s Precious Little Life, published a mere eight months after Lost at Sea, features a brash hero who doesn’t seem as introspective as Raleigh, who isn’t constrained by imaginary boundaries and doesn’t even seem to realize real ones. I adore Scott Pilgrim, but I never thought he was secretly me. I’m sure a lot of this has to do with gendered personality differences, but I’m convinced it’s also a function of narration. Unlike Lost at Sea, Scott Pilgrim is a third-person story. Scott is the protagonist but not the “I” of the story; its “I” is the reader, who gets a little help from my good friend focalization. We don’t see what Scott sees, but we get plenty of opportunities to experience how he sees his world.

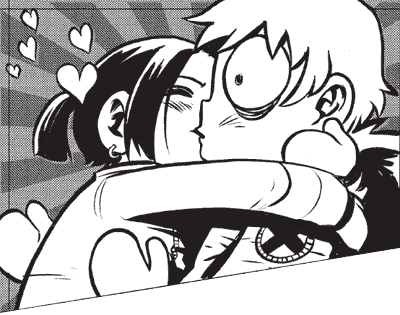

This, too, is a subjective story, but unlike the empty eyes Raleigh sees and her worried musings about her surroundings and background, Scott’s world is vibrant and dramatic. Scott doesn’t narrate his life so much as stage it, and Scott Pilgrim is a prime example of the way comics, like films, can focalize powerfully. Everything we need to know about Scott’s understanding of himself as he meets Knives is encapsulated in this image that isn’t a god-view but a non-view, a skewing of the events in a way no one saw them but instead as Scott (and, at least in his mind, Knives) experienced them. This is third-person twisted storytelling, not limited by the range of what Scott knows and tells, but blown open by the lack of limitation he finds in his experiences. We readers can be Scott without being inside him, see how captivating but also how thoughtless he can be while realizing that he’s aware only of the first of those traits. This simultaneous flexibility and distance is really a strength, I think. Raleigh’s insistently idiosyncratic voice could put off readers unlike me, readers who found her immature and self-absorbed in a way that didn’t make them think of themselves, because there’s no way out, no alternative to her view from the back seat. Scott, on the other hand, isn’t the only persona strong enough to get an angle on his story. Would he be the one to focus on the apartment ownership chart? (Well, maybe, actually, but Wallace is presumably well aware of the unequal distribution of labor and resources.) His highschool girlfriend Knives takes the initiative to kiss him and to worship his band, and if Scott ruled the world those things wouldn’t happen, but his is a contested reality, with another subjective look at the world always threatening to seep in. And really that’s what Ramona is, not a dream personified or deferred, but a person with views and a past whose very presence upsets Scott’s daily (and nightly) world. Really all the women in his life are potential strange attractors, strong characters with a lot of pull and depth, but perhaps gender is best left for another day.

For now I’m more interested in what seems like a leap in sophistication from Lost at Sea to Scott Pilgrim, although that may not be a fair characterization. They’re such different works with different perspectives and looks, although both address similar quests and worlds. Raleigh is like Knives and her friends, excited but inexperienced, ready to break out into a world of passion and danger, while Scott thinks he’s lived that all already. But each is about how difficult it is to come to terms with ourselves and all that that means. For Scott, the best fighter in the province, this may mean becoming a knight who battles for the honor of his lady, although I imagine what he learns in the process will be more interesting than the fights, cunningly staged as they may be. For Raleigh, personal change means not becoming more disciplined but opening up, being willing to trust people to be people rather than just what she expects them to be. For me, it’s something in between. Like Raleigh, “I look in the mirror and think I don’t belong there.” Like an embarrassed Scott, I sometimes think, “I’ll leave you alone forever now.” But all I’m really trying to do is create some kind of sense and meaning out of the world and myself as much as I can, and I know that’s not the kind of story that has an end, and that’s the kind of story I like best.