“I was sentimental—back when I was old.”

At first, Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again reminded me of Gigli. No, seriously. Gigli is a movie in which some parts are good, other parts are good but you find yourself asking “Why the hell’s that in this movie?” and other parts make you hope they’re an absurdist parody but you have this horrible feeling the director actually wants us to watch that final scene with the mentally retarded kid whose only dream in life is to meet the hot babes of Baywatch and find it touching and heartwarming…

So DK2 was like that, except mostly scenes in the latter two categories.

Now I think that’s probably much the effect Frank Miller and Lynn Varley were going for. (Miller and Varley are both listed on the front cover, and Todd Klein is listed just below them on the title page, no information about what each actually did on the book, which I think is neat because the message seems to be “We are all equally authors of this text” but I suppose it would be annoying if you didn’t already know who each author was and which parts of the text he or she contributed. At any rate, hereafter I’m going to go auteur and refer to the “author” as “Miller” and “he.”)

Something just occured to me: the plot, such as it is, of DK2 involves Lex Luthor and Brainiac faking an alien invasion to maintain their control of the populace (and to kill off the pesky superheroes). Sound familiar…? Yeah, Watchmen! An allusion? I think so. And DK2 pretends to be a sequel to Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, but it really doesn’t work as a sequel—it’s more of an extended allusion ot DKR.

How would you feel if you fancied yourself something of an iconoclast in the realm of superhero comics, somebody who’s not so worried about preserving traditions, who in fact likes to kick tradition in the ass and go looking for fun new stuff… and you found that people have canonized a comic you created 15 years ago? You’d feel a lot like Frank Miller must have when he decided to write DK2, I bet. Miller doesn’t strike me as the sort who likes his books to be safe. But DKR is second only to Watchmen in safeness—not that either of these books is safe or comfortable if you read them and pay attention, but they’re safe in that they have such a status among comics readers that they’re practically untouchable and most negative criticism is met with indifference at best, even though many readers would probably be hard pressed to explain just why they’re so great without resorting to mumbling about “deconstruction” and other fancy words they probably can’t define. They’re respectable comics.

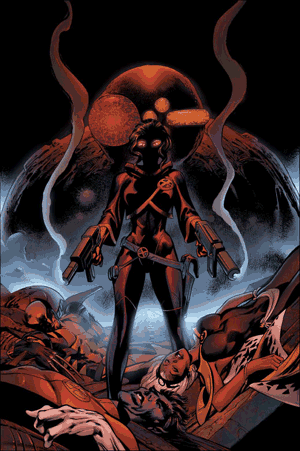

Canons and classics are just fine, no doubt about it, but if you revere the canon at the cost of ignoring other good new comics, comics will stagnate. How many times have you heard somebody say “There has never been a comic since Watchmen that was as good as Watchmen” or “Watchmen is the best comic ever written”? I’ve seen lots of people say things like that, and it’s bullshit. There have been piles and piles of superhero comics as good as or better than Watchmen and DKR. Miller doesn’t want to be safe and respectable, he wants to kick tradition in the ass and blow up icons. DK2 is his powerful projectile aimed directly at the reputation of DKR. The projectile is… Superman and Wonder Woman, united in carnal embrace.

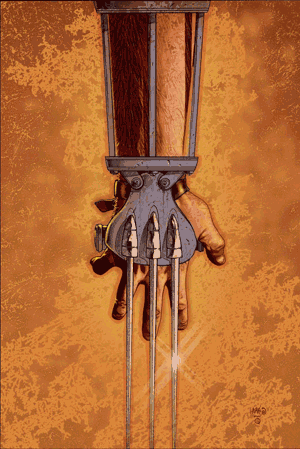

If you haven’t read DK2, trust me, you have to read the Wonder Woman-Superman sex scene yourself to grasp its full impact. Superman has just been beaten up by Batman, blown up by the Flash, shot full of Kryptonite by Green Arrow, and had the Atom inserted directly into his brain: he’s in bad shape. Wonder Woman finds him at the site of the erstwhile Fortress of Solitude and berates him, saying among other things, “Where is the hero who threw me to the ground and took me as his rightful prize?” Yes, Wonder Woman, doing a Red Sonja act! Then she and Superman fuck each other’s brains out so hard that, I’m not kidding folks, they cause catastrophic seismic and weather disruptions across the entire world. If your reaction as you read this passage (pp. 111-124 of the trade paperback collection) isn’t something like “What the fuck???” then you are entirely too jaded for your own good. And that’s exactly the reaction Miller’s going for. Whether you think it’s good reading hardly matters (I do not think it is good reading, I think it scarred my poor innocent brain for all eternity). What matters is that Miller has broken free of the limited bounds within which Superman and Wonder Woman had been allowed to operate. DK2 has many other more, dare I say it, subtle ways of breaking free, like giving Superman and Wonder Woman a daughter (who, in one of the book’s best scenes, demands that Superman tell her about Kryptonian sex).

If I haven’t made it clear, I had a lot of fun with DK2, although to a certain extent it’s not a book that was designed to be liked (at least, not liked by everybody). The fact that so many people hate it is arguably a sign of success—I suspect Miller deliberately wrote a book he knew a lot of people would hate, not just to screw with his fans but as proof against it’s ever losing its edge and becoming safe and comfortable.