Unfortunately, I think Nate Bruinooge over at Polytropos has it right about Quentin Tarantino and Kill Bill:

Another, darker failing of his that has finally become clear to me is this: he finds abhorrent violence terribly funny. One of his strengths has always been the fact that he does not sugercoat violence, or pussyfoot around its most graphic and troubling aspects. He doesn’t allow us to get comfortable. But I’m afraid this may be accidental, because for him the violence we’re talking about — a goon splurting blood from a lost limb, a woman thrashing on the floor after losing her last eye — is already comfortable for him. If this is true it is rather damning of the man, not necessarily his work, though this particular movie seems to be a clear expression of his personal quirks unfettered by editorial critique or high inspiration.

I really only have one thing to say about Kill Bill Vol. 1, I guess (I’d probably have more to say if I watched again): OK, Buck? Who likes to fuck? How the hell did this shit not end up on the cutting room floor? It’s stupid, it’s nonsensical, it’s one of the most repugnant comedic-abhorrent-violence scenes in either volume of Kill Bill. Kill Bill Vol. 2 makes even clearer how wrongheaded the chapter is—it’s totally self-contained, it has nothing to do with the rest of the story (except for mild jokes about the Pussy Wagon), it serves only to dilute the sexualized violent relationship between the Bride and Bill. It turns the Bride from a person who was specifically victimized in specific ways by Bill into a general sexually victimized woman. With the Bride and Bill, you don’t have to read it as some kind of commentary on gendered violence or victimization of women or something, but the Buck chapter pretty well requires a reading pertaining to those themes, since there’s zero characterization of Buck or the trucker rapist or the Bride anywhere to be found and so there’s nothing to think about but the general gender politics. So are we supposed to cheer or something when the Bride eats off her rapist’s face? Jesus. And then we have to say… Well, gee, is the whole movie about violence against women or something? Is it supposed to be some kind of statement about victimization of women in action movies? Or is the Buck chapter just stupid and nonsensical and totally unrelated to everything else?

Is the movie a repugnant statement or is it just badly designed?

Well, anyway, here’s what I think about Vol. 2:

The best scenes in the movie manage to be at once trite and powerful. Most of them involve little B.B. Take the scene in which Bill explains to B.B. how he shot Mommy. The dialogue goes something like this:

Bill: I shot Mommy right in the head.

B.B.: Why, did you want to know what would happen?

Bill: No, I knew what would happen to Mommy when I shot her in the head. But what I didn’t know… was what would it would do to me.

B.B.: What did it do to you, Daddy?

Bill: Well, it made Daddy very sad.

It’s totally ridiculous and trite, but, well, it’s true, in a way. Tarantino uses B.B. to let his characters say things he could never get away with otherwise. They’re talking to a child, so they can talk like children. I said the stuff like this is trite, but also powerful, because it cuts right to the core of a lot of action movie morality, which is often painfully naïve. Take John Woo’s The Killer. Where did I just see something insightful about John Woo? Ah, right, from Dave Intermittent, in an attempt to formulate a taxonomy of martial arts action movies:

The second type [of martial arts movie] is played straight. Which is not to say realistic; but it takes its own absurdities very seriously. It doesn’t wink at the audience. And because it takes itself seriously, it can reach for something beyond simply entertaining an audience. Its lunacy becomes contagious; it can aspire to narrative power. Think about (not a kung fu movie, but the point remains) John Woo’s Hard Boiled. It makes, frankly, no sense at all, either in its narrative or its physics. It’s honor/betrayal paradigm shouldn’t really work, given what its yoked to; and explained to people who haven’t seen the film, it often doesn’t. But as a movie…it works. Oh man, how it works. It works because Woo never doubts that it should work, or lets on that he knows it shouldn’t. Woo never admits that his films are cartoons, and his belief that they aren’t transmutes them from cartoons into something more.

The Killer is another great example of this kind of movie. Woo obviously wants The Killer to be a tragic movie about violent people whose lives and the lives of the people they love end in horrific violence, but the thing is, the violence looks so damn fun! It’s exactly like a bunch of children playing cops & robbers or cowboys & injuns or the simplest, purest version of childhood violent play, the immortal Guns. Do children still play Guns nowadays? Just run around shooting each other, great fun. Kill Bill seems to want to acknowledge the childlike (childish?) quality of play in action movies, most obviously in the toy guns scene. Beatrix has tracked Bill to his home, she stalks through it looking for him, she steps onto the back porch… where Bill and B.B. stand holding toy guns. After some dramatic narration by Bill, B.B. fires her weapon: “Bang bang, you’re dead, Mommy.” Then Beatrix just stands there, looking at her daugher for the first time in both their lives, and this one closeup of Uma Thurman lasts maybe five seconds, and damn if that’s not about the hardest five seconds of film to watch that I’ve watched in a while. And ooh, Tarantino gets it, he’s taken the unconscious childlike-play metaphor of so many action movie gunplay scenes and literalized it. OK, sure, he falls victim to the same childlike ecstasy of violence in this very movie, but really, what an interesting way of dealing with it—put an actual child in the movie and let’s see if we can turn those trite statements about violence into something profound(ish). Maybe. Then I just now thought, “Yeah, but this is the same movie (OK, same two movies) with Buck Who Likes to Fuck, remember?” and that sort of ruins the effect, I have to admit.

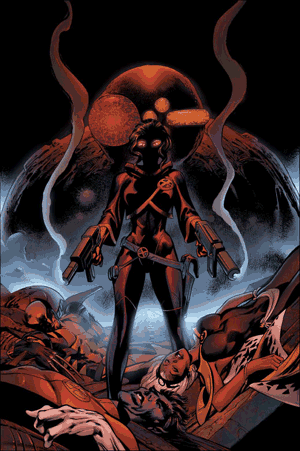

I liked the goldfish scene, too, its parallelism with the Elle Driver scene. Elle is the goldfish outside its tank, flopping around after Beatrix pulls her eyeball out. Then Beatrix stomps on the eyeball—just like B.B. stomped on her poor goldfish. Yeah, trite and obvious, but that’s what we’re going for here.

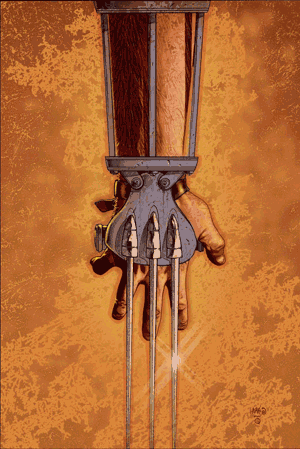

Speaking of Beatrix… Beatrix? Beatrix Kiddo? I didn’t get the “Trix are for kids” joke until Rose pointed it out to me, and now I wish she hadn’t, because damn. Why is “Beatrix Kiddo” bleeped out in the first movie? What’s the allusion (there must be one)? Does it have anything to do with anything other than being an allusion? Some of the pastiche works as part of the text—Rose talks a bit about how the Western stuff works—but too many of the references seem to exist only as references, so that the text becomes sort of a laundry list of movies Tarantino has seen. The name-bleeping may not be the best example, because there’s a lot of reasonably good stuff about names and identities (the Superman speech! another pretty good scene) and the name-bleeping probably ties in to that. Still. Other seemingly pointless allusions apply. Am I supposed to be impressed that Tarantino has seen every single movie ever made? How boring. Why don’t I just watch the actual Once Upon a Time in China and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly instead?

Kill Bill frustrates me, you may have noticed. The more I want it to be a good movie, the more I wonder if it doesn’t want to be a good movie.

It does have some amusing dialogue, though.

Budd: She’s got a Hanzo sword?

Bill: He made one for her.

Budd: Didn’t he swear a blood oath to never make another sword?

Bill: It would appear, he has broken it.

Budd: Well… maybe you just tend to bring that out in people.

The Bride: You good with that shotgun?

Janeen: Not that it matters at this range, but I’m a fuckn’ surgeon with this shotgun!