Kill More Kill Bill PSAs!

Sean Collins annoyed people this morning by saying that Kill Bill detractors should be ignored because they’re misunderstanding a great movie. I disagree with Sean that any of the characters renounce violence, except maybe the Tiny Yakuza who brings out Beatrix’s motherly side. And if they don’t renounce violence, are they all getting punished? Actually, I realize what he said was that “characters who refuse to renounce violence and deceit are inevitably punished for that refusal.” So maybe Beatrix escapes on a technicality for not managing to tell lies while dosed with truth serum, and limbless Sophie Fatale didn’t become headless too because she’s a coward who squealed. But that’s not what I’m focusing on here.

In an email, he clarified his thoughts on the aspect of sexual violence that had bothered Steven and me:

Anyway, I’d talk about the sexualized and exploitative violence–if, that is, I thought there was any, which I didn’t. Not all violence against women is sexualized, and I didn’t think any of it in Kill Bill was. No fetishizing shots of breasts, nipples, legs, crothces, asses, or even hair, really, just by way of a for instance. At any rate, it’s tough to think of a stronger female character than the Bride, who’s easily the best action heroine ever (depending, I guess, on whether you like her better than Lt. Ellen Ripley).

So maybe it boils down a problem with definitions, what makes some violence sexual and some not. I didn’t mean the violence was problematic because it involved femmes fatales in boob socks, which seems to be Sean’s definition of sexual violence. Well, I say it’s spinach and I say to hell with it. Without talking about which “worked” for me as story elements and which didn’t, I’m going to make an incomplete list of categorically grouped sex-related violence from both my hazy memories of Kill Bill Vol. 1 and the more recent volume.

There’s some straight-up sexual violence. Buck has been accepting money to let men rape Beatrix while she’s comatose. I’d argue that the murders in response to this fall in the same general category. Beatrix has no reason to murder these two men except that she’s been their victim, so she’s trying to “right” the power balance because there’s nothing she can do about the sex part, which of course is the point. And Esteban slicing up the faces of his prostitutes, that seems like violence as payback for infractions related to sex and power, though we never learn the details.

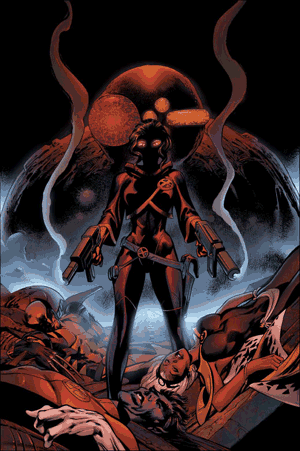

Then there’s gender-based or sexist violence. When Gogo slices through the businessman who propositions her, she’s upsetting social norms and doing something unexpected for a woman. She’s penetrating and controlling someone who sought to do the same to her. O-Ren has to do the same thing, beat the men at their game of brutality to lead the Yakuza. If Bill is to believed, Pai Mei is a sexist who makes the women in his tutelage work harder and suffer more to prove their ability.

And there’s no lack of violence in/and romantic or just sexual relationships. Maybe Esteban’s role as a sometimes violent pimp fits better here. I don’t just mean standard intimate violence, but the way sex and violence are intertwined for the characters. Elle kills Budd so she can take credit for offing Beatrix, thinking it will endear her to Bill, not to mention knock out a rival for his affections. And when Elle and Beatrix finally fight, is the extra brutality payback for old hurts or the old girlfriend going after the rival who’s taken her place? Most obvious, though, is that Bill and Beatrix were obviously having sex, and Bill killed Beatrix after she left him. Whether or not it had to do with his jealousy that he was being replaced in her heart and womb, when you kill someone you’ve been sleeping with, it’s intimate violence and it’s not uncommon in our world either.

Objectification seems too subjective to catalogue and was something I didn’t find too problematic, perhaps because it’s what Tarantino understands best. I thought the parallel between the prostitutes in the brothel and Bill’s Assassin Squad was an insightful one that added depth to the story. And I haven’t quite figured out the mechanics, but I liked the way Budd didn’t objectify the strippers he worked with but did treat Beatrix as subhuman when burying her. He treats women who are nothing more than puppets in the movie as characters and belittles (and thus underestimates) the two fully realized women he deals with in the movie.

I’m sure if I spent time thinking about it I could come up with more than this, but there isn’t much of a point. These are issues that hit close to home with me, so I know I’ll be more strongly affected by them than most viewers, but I don’t know how anyone could ignore them all or be unaffected by them. I didn’t think the movie was necessarily exploitative in a porny way, making Uma Thurman some kind of fetish object, but the violence exploited the audience.

Sean also says he’s avoided analyzing Kill Bill Vol. 2 because he likes it too much to have critical distance. I hope he reconsiders, because I think I can see what aspects people would like, but I’d love to hear what they actually are. It’s usually easier to do negative reviews and it can be difficult and self-revealing to talk in any detail about what you like. One of my goals in writing here is to get more comfortable doing both sorts of reviews. I’m still working on that part, but apparently have no qualms about pressuring others to do what I don’t. And Mr. John Jakala, this means you! We who haven’t yet seen Dogville want to know why we should!