12 January 2004 by Rose — Filed under Comics

[Edit 2004-01-12 2:30 am UTC]

To respond quickly to Dirk Deppey’s response to my response to him, I think (and thought then) that we are basically of the same opinion, but I haven’t dropped my quibbly attitude.

As far as I could tell from a cursory reading of John Byrne’s rant (and I wouldn’t want to give it more thought even if I were able to think beyond when I can take another decongestant pill and whether I’ll be able to breathe clearly enough to sleep tonight) the entire focus of the argument was on trade paperback collections of mainstream comments “mainstream” comics. Even the passage Deppey quoted, Byrne’s statement that trade-only publishing would be too expensive for companies to handle and have too little return in terms of drawing in new readers, need not be read as talking about anything more than the mainstream “mainstream” comics market. I assume Byrne does realize that people are buying and reading Blankets and Persepolis and that this is just not what he’s talking about. He’s questioning whether I would have paid $20 to buy Batman: Hush, had it been on the shelf beside Persepolis. In this case, he’s right. I, although not John Byrne’s Platonic Ideal Comics Reader, would be more likely to buy a $3 pamphlet or a minicomic to see if I can get a taste for a creator or story before investing more money and time into it. However I’d be even more likely to pick up a promising trade paperback or graphic novel for free at the library, where pamphlets aren’t readily available, and have bought books based on that. This is how I deal with much of my word-only book purchasing as well, since I want to buy books I’ll lend and read again.

To get back to Dirk Deppey rather than John Byrne, the point I was trying to make and, I think, didn’t is that different genres (or whatever word you’d like to use) employ different marketing strategies. Graphic novels don’t have to be composed of previously released smaller parts, but that’s one way to do it. I’ve read plenty of novels that began as short stories, or that contain previously published short stories, sometimes because I enjoyed the initial story so much that I sought out the larger context. In choosing the examples he did, Deppey actually gave a good implicit rundown of possible alternate, pamphlet-free routes to the graphic novel, which is what he was trying to do. I just think that they’re not what John Byrne was arguing against, and I was saying that having cartoons in Time or multiple reviews and interviews in The New York Times or a highly acclaimed first graphic novel can be seen as (loosely) functional equivalents to having previous pamphlet stories act as teasers for a trade paperback. I just still don’t think this makes what John Byrne said about mainstream superhero trade paperbacks wrong. I’m fully willing to believe he is, although I don’t know the economic details to know whether he’s right on that front, but I still don’t think the existence and success of graphic novels that appeal to a real mainstream readership, or at least some interested subsegment thereof, as opposed to “mainstream” superhero comics readers is actually a refutation of his argument at all.

2 comments »

10 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics

Dear Readers, I need some quick research help. I want to map out how the X-Men high concept has evolved since its beginning, but I don’t want to have to buy and read every X-Men book ever—I just need the highlights. The only X-books I’ve read are New X-Men and X-Statix, so I’m look for other books of interest w/r/t the evolution of the X-Men high concept and the metaphors used in X-books. By “evolve,” I don’t mean “improve,” I mean “adapt to its current context.” E.g., the X-Men began as the Children of the Atom, I believe with the implication that mutation is caused by atomic radiation (surprise, everything is caused by radiation in that era of Marvel). How has the portrayal of mutation changed over the years? And just as importantly, are there stories (preferably ones available as TPBs) that exemplify various stages of the evolution of the mutation concept? I know I should look for the Marvel Masterworks or Essential X-Men. I’m also interested in the evolution of the metaphors in the X-Men. We’ve discussed that some already on the blog, w/r/t race, feminism, geek pride, more general political metaphors. Anything else interesting I might look out for? Are there 1960s-era stories that are especially metaphorically interesting?

3 comments »

9 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics

While I’m posting comics, here are a couple more I’ve done:

Comments disabled

9 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics

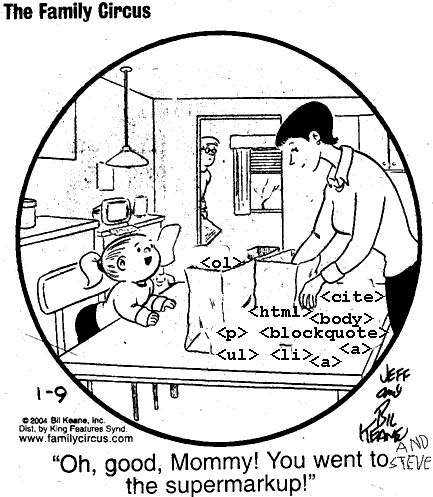

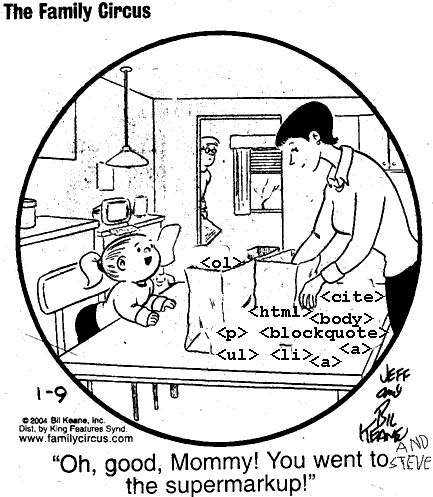

Yes, that is the actual caption on today’s Family Circus. Is it a joke about supermarkets marking up their prices? I do not know. Now it’s an HTML joke, go me.

Comments disabled

9 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics

Thank you, Steven Wintle: Wonder Woman #246 is on my must-find list!

The Amazons don’t have good fabric softener! Who wrote this brilliance? Jack C. Harris.

Comments disabled

8 January 2004 by Rose — Filed under Comics

Dirk Deppey sez, in attempting to refute John Byrne’s arguments against original graphic novels (a noble, if not difficult, endeavor):

Moreover, consider the notion that no one will pay for a $20 book without having read it in pamphlet form first. Can anyone who’s given the bookstore market even a cursory examination do anything but laugh? How does Byrne think hardcover prose novels sell? The argument’s equally idiotic where graphic novels are concerned. Picture Craig Thompson, Joe Sacco and Marjane Satrapi smacking their foreheads and crying, “Why, God, why didn’t I listen to John Byrne when I had the chance!?!” Mind you, Thompson, Sacco and Satrapi produce works that the average person in the street might actually want to read…

While I understand the argument he’s making, that people choose what to read largely based on reviews and recommendations rather than just wanting extra copies in different formats of books they’ve already read, it might have been a bit stronger if more than one out of the three examples worked primarily in original graphic novels. Maybe 1.5, if we count making two volumes of French Persepolis into one book for the anglophone market as still dealing in graphic novels. It’s a story told in segments, of which the version I read is one, but so are its constituent books and the other parts of the series. Maybe the issue is that 80 pages in French b/w does not a pamphlet make? I don’t know how anyone could claim Sacco was saving is work for his graphic novels, though, since Safe Area Gorazde (and I apologize to any linguistic purists that html doesn’t seem to allow me to use the proper “z”) had the preceding comics journalism he had published in various venues during the war serving as a teaser for discerning readers and Notes from a Defeatist is a collection of previously published works. I don’t follow Deppey closely, though, and I’m not sure how limiting his definition of a graphic novel is. Is Persepolis a limited series? Is Notes from a Defeatist not a graphic novel in that it’s not a novel by standard criteria, whatever those are? I really don’t know and it’s not a question that interests me.

Anyway, yes, it’s good that people read works that are interesting and getting a lot of critical attention, like the books of all three cited writers. I also believe it’s bad to take John Byrne seriously, but perhaps someone’s gotta do it. The truly horrifying thing is that people do, and concur.

And on a last and unrelated note, Deppey says Byrne “stands athwart history and says ‘Stop!’” a quick search shows that perhaps Byrne should have been yelling, but maybe he just doesn’t have as much energy as the young William F. Buckley, Jr. I’m frightened I caught the reference and want to know whether it was supposed to have political implications about Deppey’s already uncloaked opinions about John Byrne or whether it’s a throwaway line. Both, probably.

Comments disabled

8 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics

John Jakala brings tidings of ugly manga art from Marvel. Mr. Fantastic is Billy Bob Thornton flashing gangsta-rap hand things!

Now, the idea behind the Marvel Age is to republish 1960s-era Marvel stories with new manga art. At least Marvel is being honest now about their creative autophagy.

2 comments »

7 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics

Jack Chick draws alien demon children. They are scary.

Jack Chick is my blasphemous golden calf.

Sez Rose:

I don’t think people who think babies get put inside people know what virgins are. Hadn’t jesus made, like, LOTS of people come back from the dead?

Yes, and yes!

Comments disabled

5 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics, Literature

Sources used in this post: Borges, Jorge Luis. Collected Fictions. New York: Viking, 1998.

How common is the idea that the X-Men are a racism/race-relations metaphor? Because I notice people seem to say it a lot (e.g. here), and why do people say it so much? I don’t see it. OK, I see it, but it seems limiting to suppose the X-Men are merely a racial allegory. There’s the gay metaphor too. But there’s more. The most common criticism of the racism and gay metaphors I see is that gay people and Hispanics don’t have superpowers. Oh, but it’s a metaphor! It’s something inside that’s so powerful, so liberating but also uncontrollable, and once you let it out there’s no going back. It’s pride, black pride, gay pride, whatever. The X-Men are a fantasy of political activism. When you’ve been silenced and made invisible for whatever reason, and then you decide to take pride in whatever makes you an invisible and you stand up and make people notice you and your pride, people will, yes, hate and fear you. That’s what the X-Men are about. I don’t see any need to make it about any one kind of pride/activism.

Does this have anything to do with my analysis of New X-Men in terms of “creation of self through narrative?” I think it may. If you’ve read any stories by Jorge Luis Borges or the novel Vurt by Jeff Noon (I’m not quite changing the subject here), you’ll probably know what I’m talking about when I say both these authors (and many other authors, but I’m using these two as an example) write fantastic narratives in which the world is a text. I mean, there is no illusion (or the illusion is exploded) that the world of the stories is “real”—the world of, say, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” is no more real than an encyclopedia, and in fact it ends up being superseded by a fantasy world described in a fictional encyclopedia article. (I have some essays on Borges’s and Noon’s work that go into more depth, I should put them on the blog at some point.) Noon especially writes a protagonist who is empowered by the realization that his world is a textual world.

Borges’s stories aren’t just clever but inconsequential metafictional games. They propose a way of looking at our own world:

Then years ago, any symmetry, any system with an appearance of order – dialectical materialism, anti-Semitism, Nazism – could spellbind and hypnotize mankind. How could the world not fall under the sway of Tlön, how could it not yield to the vast and minutely detailed evidence of an ordered planet? It would be futile to reply that reality is also orderly. Perhaps it is, but orderly in accordance with divine laws (read: “inhuman laws”) that we can never quite manage to penetrate. Tlön may well be a labyrinth, but it is a labyrinth forged by men, a labyrinth destined to be deciphered by men.

Read the rest of this entry »

3 comments »

3 January 2004 by Steven — Filed under Comics

…well, let’s just say some of us were born to kill and raised to kill and that’s the only damn thing we’re any good for. Everything else is just lies we tell ourselves.

(There are some New X-Men spoilers lurking in here.)

This is the beginnings of what I think will become an actual essay, with footnotes and everything. I am intrigued by Grant Morrison’s New X-Men, but I’ve not seen a lot of discussion on the Internet about the things that intrigue me (maybe I’m looking in the wrong places). What intrigues me is analyzing New X-Men in terms of Rose’s theories about narrative art, specifically creation of self through narrative. We’ve been talking about this a lot lately, and I noted that many (all?) the example narratives we came up with to talk about have as a central conflict the problem of who controls the narrative. I haven’t seen Capturing the Friedmans (which Rose talks about in that post I just linked to), but I gather that control (and ownership) of the narratives of people’s lives is at stake in that story. Paycheck (which Rose also discusses) is hardly about anything coherent, but it’s based on a Philip K. Dick story (Dick’s stories are incoherent in a much more interesting way than Paycheck the movie), and Dick was always writing about characters losing control of their narratives.

Right, I think New X-Men is about characters attempting to create themselves by creating narratives, and it’s about characters losing control of those narratives. Charles Xavier loses control of his political dream to his evil twin. Henry McCoy tells his ex-girlfriend a little lie and tries somewhat unsuccessfully to turn it to his advantage when it spirals out of control. Emma Frost convinces herself she’s a good teacher, a good lover, a nurturer, a strong independent person, only to see her life shatter around her. Quentin Quire, after his life is turned topsy-turvy by the revelation that he’s adopted, constructs a new life for himself out of every possible troubled-teen warning sign and teen-movie cliche (using drugs, bullying, getting in fights, rebelling against authority, turning to radical politics, trying to impress a girl, and much much more) but can’t control his own inventions. Scott Summers is deeply unhappy with his own (non-)personality but can’t manage to do anything but stand still as his life goes to hell. Weapon XV bursts through the dome of the World, transcending what was the whole of its existence, only to bindly acquiesce to the controlling forces he finds beyond. (If there are forces beyond comprehension (a military science team running the World, an omniscient god, anthropological determinism, the writer) that know the narrative better than we, can we have any control?) Wolverine gives up control of his own narrative—decides he’s the killing machine Weapon Plus says he is and can’t be more or other than that. So there are all these stories about loss of control and it’s not just control of power, but control of choice, of selfhood, of the right to be the narrative subject. Loss of control over the narrative of their lives.

There are several things I’ll be thinking and writing about, in addition to setting out arguments to support my thesis:

- X-books may be read as very political. What are the politics of New X-Men, what do they have to do with creation of self through narrative (or failure to create self through loss of control of the narrative)?

- New X-Men seems optimistic and hopeful (particularly in terms of the X-Men making progress in their political goals), and a lot of people seem to respond strongly and primarily to this in their readings. What’s the relationship between the surface political optimism and the darker themes of loss of control?

- The aesthetics, particularly of the art. What does the sequential-art form do for the text in terms of the narrative themes?

One comment »